Equality and Justice: The Flowchart

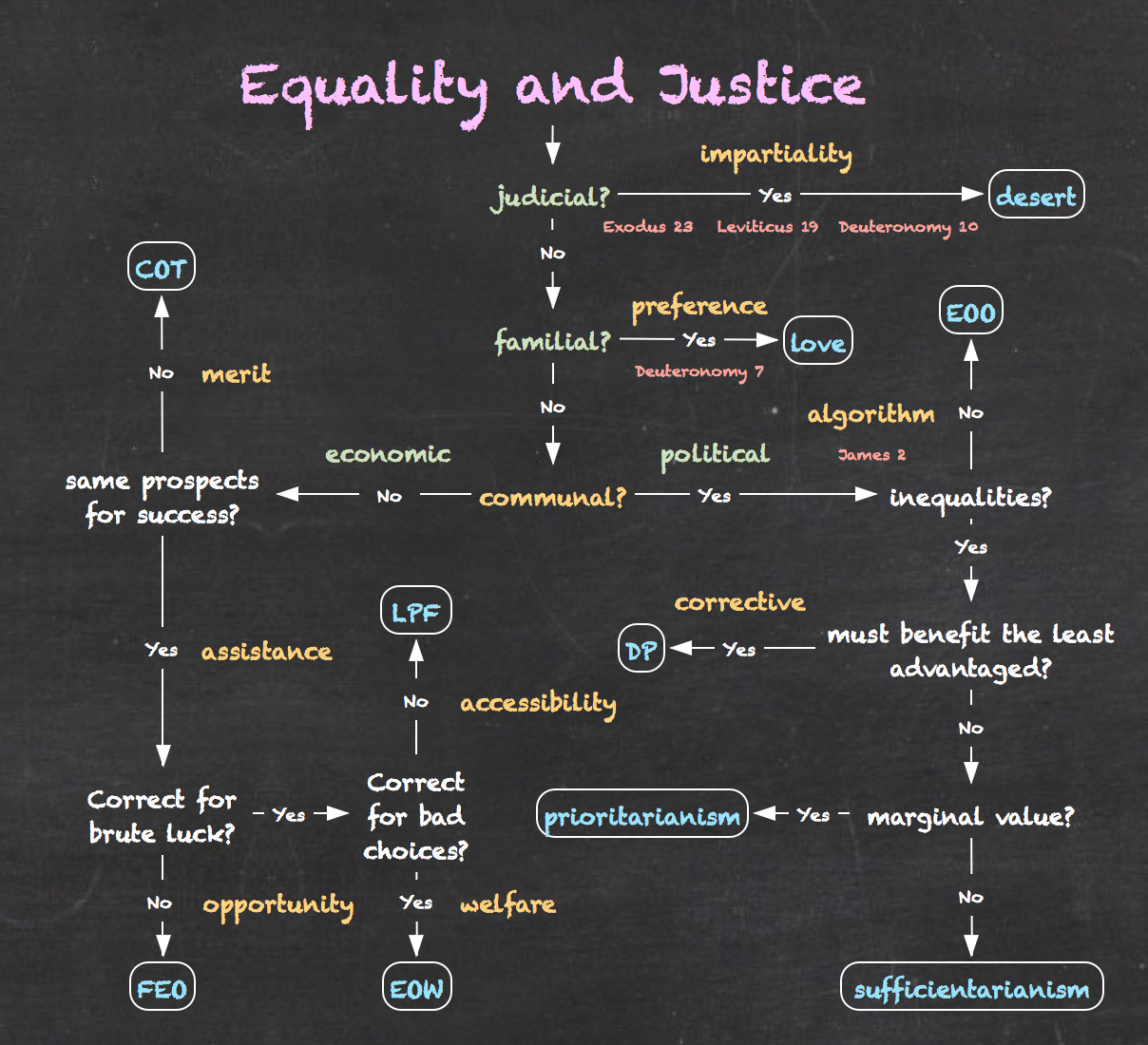

We all want justice, but we have different ideas about what justice requires. I am convinced that thinking about justice’s relationship to equality can help, hence this flowchart.

We all want justice, but we have different ideas about what justice requires. It is hard even to know how to start a more careful examination of what we believe. I am convinced that thinking about justice’s relationship to equality can help. In this flowchart I trace different paths through the labyrinth of equality and justice. I simplify distinctions, remove some possible detours, and generally resist the temptation to make caveats at every turn because, if I did so, it would be even more confusing than it already is.

Let’s walk through the labyrinth together and learn more about what we think justice requires in any particular situation. I’ll be sure to give you the relevant sections of the flowchart as we go along.

Top of the Flowchart: Settings of Justice

First, in green text, we have four options for what I’ll call the setting of justice: the judicial, familial, economic, and political settings of justice. What we think about equality and justice can vary depending upon the context. These four terms may describe actual settings, or they may serve as placeholders for your thinking about the situation. For example, disciplining a child may be considered judicial even though the relationship is familial.

If you are a judge in a courtroom, you must uphold the rule of law. Desert, not socioeconomic status, should determine the outcome of the case. The question is not whether a man is poor but whether his cause is just. Judge with impartiality! That’s the imperative. The Bible supports this formal equality: Exodus 23, for example, says neither to “pervert the justice due to your poor in his lawsuit” nor to “be partial to a poor man in his lawsuit.”

By contrast, if the setting is a family, equality and justice play different roles. Far from thinking someone is doing injury, harm, or an injustice by preferring one child to another, we expect and approve of preferential love in the context of families. If a man loved every child as much as his own, it would not only be socially awkward, it would be harmful to his own children — and possibly to other children as well.

Finally, we can talk about justice and equality in the marketplace and in politics. To do so, we will need to explore the lefthand and righthand sides of the flowchart.

Lefthand Side of the Flowchart: Markets

Let’s talk about the market first. Most people think we should have some kind of equal opportunity in employment, but we disagree strongly about what we mean by that phrase.

Minimally, most people accept careers open to talents (COT). The most qualified applicant at the moment of hiring should get the job. True, people don’t have the same prospects for success (e.g., some had expensive tutoring while others went to horrible schools), but that doesn’t matter for the sake of justice in hiring. We can’t, or shouldn’t, correct for such things. We should just give the job to the best qualified person.

If you think justice demands more — that equally talented and ambitious people from different socioeconomic backgrounds should have the same prospects for success — you believe in fair equality of opportunity (FEO). We should assist the economically unfortunate and give them a better chance for success than they would have on their own.

Perhaps you think even more is required. If you think justice demands correcting for bad luck (a philosophical phrase — I don’t believe in luck), like a disability, then you believe in a level playing field (LPF). You think we should give people more than mere assistance for opportunity; we should also give them access in spite of their disabilities.

Some think even more is required. Let’s say that, in addition to correcting for bad luck, you think we should correct for bad choices. If so, then you believe in equality of opportunity for welfare (EOW).

That’s all very confusing, isn’t it? It is, precisely because our intuitions about justice and equality are so confusing.

Concrete Cases

Let’s think about concrete cases. If someone commits murder, but happens to be wheelchair bound, most people don’t think that being in a wheelchair acquits one of murder. Equality in the courtroom requires impartiality. Conversely, if the most qualified candidate for a job is in a wheelchair, most people think that justice demands giving that person the job over lesser qualified applicants. That sounds like careers open to talents (COT).

But what if being in a wheelchair makes the applicant’s ability to do the job slightly more difficult, or less efficient? What if the person was born with the disability? What if he became disabled though his own negligence? We have considerably less agreement about these different cases, and it makes figuring out what is just and unjust more difficult.

Righthand Side of the Flowchart: Politics

Perhaps the market is an insufficient guide, or an inadequate metaphor, for our thinking about equality and justice. Maybe we need politics. That’s another main branch on our flowchart.

The first question in this line of reasoning is whether or not inequalities are appropriate or permissible. Perhaps one’s intuitions go strongly in one direction or another — equality always or equality never. But, as with so many things in life, most of us would say it all depends.

If someone gives me ten candy bars before I teach a class of ten students (without further instructions), my first inclination would be to offer one candy bar to each student — that is, equality of outcome (EOO).

But that’s an unusual case. We usually tolerate, and even expect, some inequalities. We expect a heart surgeon to make more money than a general practitioner, all things considered, because heart surgery requires more expertise and training — and a much more demanding schedule.

We can ask, though, whether these inequalities should benefit the least advantaged. If we think they should, we endorse the difference principle (DP). The Occupy Wall Street protestors may have been chanting the difference principle without knowing it: The top one percent can have lots of money, but they can’t have so much money if it doesn’t help the down and out. That’s the difference principle.

Not everyone accepts the difference principle. Indeed, you can reject it and still think we have a duty to help our fellow citizens. If you think there’s a threshold above which all citizens should be, you endorse sufficientarianism. If you think priority should be given to the least fortunate — that there’s a value to lifting people above a mere minimum threshold — then you embrace prioritarianism.

Understanding our Disagreements

How can the flowchart help us? For one thing, it can help us understand our disagreements. Someone with a different position may not disagree with you about the facts. The person may think, instead, that justice is best served by shifting the setting of justice away from your own preferred approach.

Take a concrete case: policing. Someone in a judicial setting will look to impartiality when thinking about police interactions with a community, but someone who sees policing from the perspective of opportunity in an economic setting will be focused instead on impartiality but on people’s prospects for a better life.

Each side of the debate can affirm the concerns of the other side, while recognizing the very real disagreement about what setting of justice settles the issue. Someone focused on whether or not a police officer actually did something in a particular instance can still express sympathy for the challenges of an impoverished and crime-ridden part of town. Conversely, someone who sees policing as a potential obstacle to the advancement of a community can still openly acknowledge that individual police officers should not be held responsible for everything bad about society. We want people to improve their lives, but we also don’t want to punish people for crimes they didn’t commit.

So I hope this flowchart can help you think through specific questions of justice. Here’s how: Take a concern that you have. Consider what kinds of questions you must answer when considering that concern. In doing so, try to locate yourself on the flowchart. That’s the setting of justice you think best answers the questions you think should be asked.

Now think about someone — actual or hypothetical — who disagrees with you. Place that person’s position on the flowchart by considering the kinds of questions that person asks in trying to address the same concern. I anticipate that rival position will be located somewhere else on the flowchart. If so, then the disagreement between you is not simply about the facts but about how to approach those facts.

Sometimes we get different answers about justice because we are asking different questions.