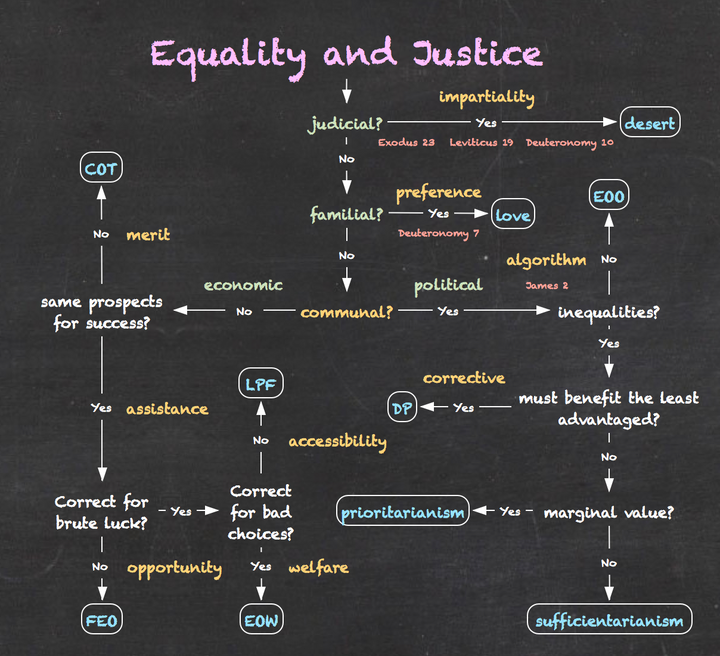

Four Theories of Justice

The four theories of justice are conservative justice, which is judicial and familial; socialist justice, which is political and familial; libertarian justice, which is economic and judicial, and progressive justice, which is economic and political.

Certain ways of thinking about justice and equality undermine historic Christian doctrines. To see why we must strain what Hercule Poirot called our “little grey cells,” reminding ourselves of the pressing importance of this issue and simply doing the best we can. We can identify four different approaches to justice and equality, which I call the four theories of justice.

Justice’s Four Settings

We start with what I call the four settings of justice: judicial, familial, political, and economic. Judicial justice looks to impartiality; familial justice expresses itself in preference; political justice focuses on the community, and economic justice focuses on exchange.

Being in a particular setting (e.g., being a father or a judge) doesn’t determine what kind of justice one will seek in the situation. A father, full of preferential love, can nevertheless see the question of punishment impartially, viewing his son’s transgression as a judge, rather than as a father. So, too, the owner of a local restaurant may look for profit in exchange (or he will if he wants to keep his restaurant open) while nevertheless hoping for, and working towards, the general wellbeing of his community.

Four Theories of Justice

These settings of justice naturally combine in a variety of ways. We’ll consider four such combinations, which we’ll call the four theories of justice.

I’ve struggled, quite frankly, over what names to give these theories. I’ve thought of offering depoliticized names to try to make things as politically neutral as possible, but doing so would make the four theories seem distant from our everyday lives, which is exactly the opposite of what I’m trying to show. So I’ve decided to give them recognizably political names, even though doing so creates two kinds of difficulties. First, it increases partisan rancor; second, it creates the opportunity for someone who has a certain political position to say I’ve misread what he thinks about justice. Well, it is what it is. We just have to do the best we can.

Here we go. The four theories of justice are conservative justice, which is judicial and familial; socialist justice, which is political and familial; libertarian justice, which is economic and judicial, and progressive justice, which is economic and political.

We can distinguish the four theories by asking two different questions. First, we can ask how they judge differences. Should we look to impartiality or to equality to answer the question of whether or not a difference is an injustice? Conservative justice and libertarian justice look to impartiality. Socialist justice and progressive justice look to equality, instead.

Second, different theories of justice take a different attitude towards the role of consent. Consent plays a role in all theories, of course. The question is whether or not consent plays a major, or a comparatively minor, role. For libertarian justice and progressive justice, actual or idealized consent plays a determinative role in deciding whether an action or situation is just. The same is not the case in conservative justice and socialist justice. We can call a need for a certain kind of consent constructivist.

By contrast, conservative justice and socialist justice think consent may be neither a necessary nor a sufficient condition for justice. Conservative justice, though seeing the importance of choices in determining moral responsibility, takes justice to be something received or recognized rather than something chosen or selected. Some things are unjust, even if people freely choose them — indeed, even if most people freely choose them.

Socialist justice — a slogan some socialists would surely reject, but a placeholder for their views nevertheless — ironically embraces a similar view. Though no friend of conservatives, socialist justice accepts that people can be hurt even if they consent to their treatment.

For example, according to socialist justice, people working in deplorable conditions can still be harmed by the injustice of working there even though they choose to work there. Something beyond their choices determines the injustice. This focus on something other than consent, present in conservative and socialist accounts of justice, is realist.

Conservative justice views justice as judgment. We don’t invent justice; we discover it, and we should apply rules without preferential treatment

So conservative justice views justice as judgment. We don’t invent justice; we discover it, and we should apply rules without preferential treatment. By contrast, socialist justice seeks liberation from oppression, and libertarian justice believes in justice as voluntariness, seeking to apply freely chosen rules without prejudice. Finally, progressive justice, similarly constructivist, nevertheless prefers equality, seeing justice as fairness.